The city of Sydney, like other Australian cities, has expanded over the last century following the garden city model of urban development, even though for some decades architects and urban planners have been fully aware of the problems inherent in this model. It is most likely that the arrival of the garden city to Australia was due not so much to its creator, the British urban planner Ebenezer Howard—whose influence could be easily established based on the colonial ties that link the United Kingdom to Australia—but rather to Walter Burley Griffin, who had worked with Frank Lloyd Wright during his Prairie House period, when he won the competition for the new capital Canberra. Until that point, both Australian architecture and urban design followed the models of the dense European city and more specifically the English Victorian model. This has resulted in a city with an extremely dense and even over-saturated centre, surrounded by low density suburbs that extend some 30 km to the north and south and some 70 km to the west. This has led to an excessively low population density, some 400 people per square kilometre, resulting in problems in energy use, travel times, quality of transport infrastructure—which in some places is oversubscribed or insufficient—the lack of urban spaces that generate urban activity, car dependence, and possibly the worst outcome, the emergence of several generations of citizens who are not sufficiently conscious of the defects of this type of urbanism and whose vision of an ideal life revolves around a house with a garden. Making matters worse, the division of the metropolitan area into several dozen town councils, with independent urban planning departments, hinders the creation of a global vision and plan for the city.

The only noteworthy changes from this model begin to emerge in the 1970's, although there were some earlier examples. The standard detached single family dwellings were replaced—sometimes in entire neighbourhoods, sometimes in single structures—by small detached residential buildings of three to five stories. It is almost as if the single family dwellings had been scaled up in size, the urban structure remained the same, but with increased density. The fabric continues to be solely residential, deprived of the activities that could generate urban life, and so the problems noted above not only remain unresolved, but actually increase, in particular those related to congestion of traffic flows. In parallel to this, "greenness" has become the main focus for some city officials, who measure sustainability and urban quality only on the basis of the amount of vegetation surrounding each building.

The project is located in Manly, an important tourist destination, especially in summer, located half an hour from the centre of Sydney by ferry. The context is an area of medium density—which follows the pattern of residential urban structure noted previously—that is the result of more than a century of interventions. This has resulted in a heterogeneous mix of architectural styles that in some cases have followed design trends too slavishly. Nevertheless, the urban structure is homogeneous, a grid of long plots with one of their short sides facing the street. Manly originally had an urban structure of enclosed Victorian blocks that has only endured in The Corso. It is the most important street, since it is one of most socially active areas, along with the promenades along the beaches. The surroundings of the site are not completely residential due to the historic nature of the area. Indeed, the current use of the site is a hotel.

In terms of the front elevation, we had to contend with city officials who were excessively concerned with establishing formal contextual relationships. As noted above, there were no reasons to justify a common stylistic basis for the area, perhaps with the exception of the principles of proportion, symmetry, rhythm, repetition and materiality of all of those buildings built before the 1950's, concepts that were subsequently ignored. We tried to incorporate these principles without resorting to imitation. In addition, city officials also required the introduction of excessive articulation and steps in the façade that endangered its condition as the main elevation—as opposed to considering it a corner elevation—which we believe the building should have. We arrived at the solution through a combination of symmetry and asymmetry and series of balconies that, without changing the frontal nature of the façade, provide movement and depth.

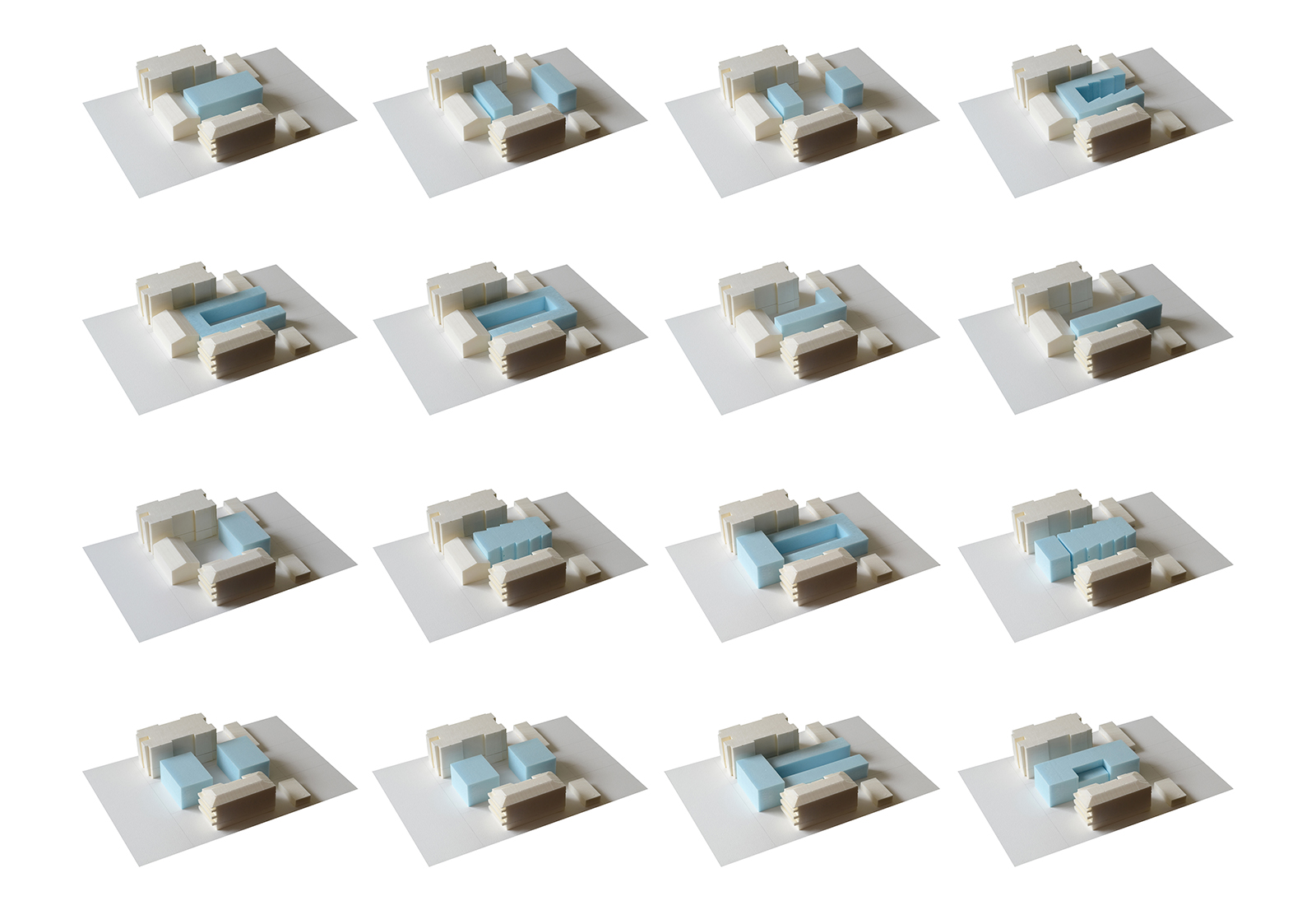

Access is through a spacious lobby that connects to a double height atrium: a space for meetings, rest, eating and contemplation. The atrium was not part of the initial sketch design, it arose subsequently as a client requirement. We decided at that point that it should have a key importance in the project, and be the main focus, in such as a way that the rest of the building revolved around it.

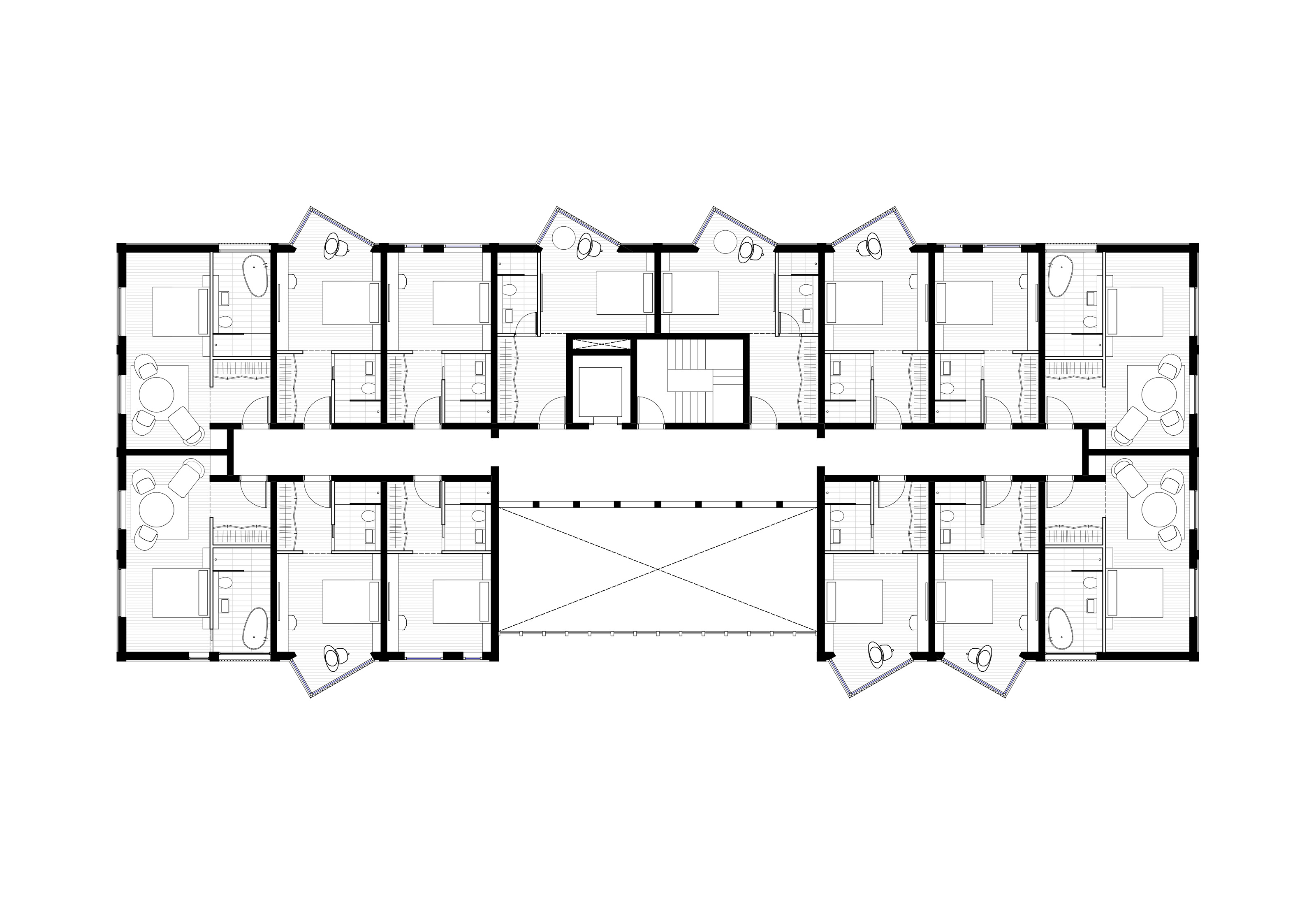

In terms of the standard floor plan, we used a typological variation, a result of our client's requirement for the rooms to be interconnected allowing them to function as one, two, or three bedroom apartments. In order to avoid the usual situation where the door that connects rooms opens directly into a bedroom, we developed a typology that allowed two or three suites to be connected by a hallway. This enabled all of the rooms to function individually or in groups of up to three bedrooms.